What can we learn from Thaler’s research in attitudes and behavioural finance? Do investors behave rationally or irrationally?

Although Dr Richard Thaler sits a few offices down from fellow Nobel Prize recipient, Eugene Fama (Nobel laureate in economics for his efficient market hypothesis) they see the world very differently. Fama sees rationality and Thaler sees irrationality. Both are right and both are Nobel Prize winners. It’s fascinating to look at the overwhelming evidence that both have produced to see how we should invest (Fama) and why investing that way is so hard (Thaler).

Ben Brinkerhoff (Consilium NZ) wrote a brief article about Dr Thaler which is an interesting read:

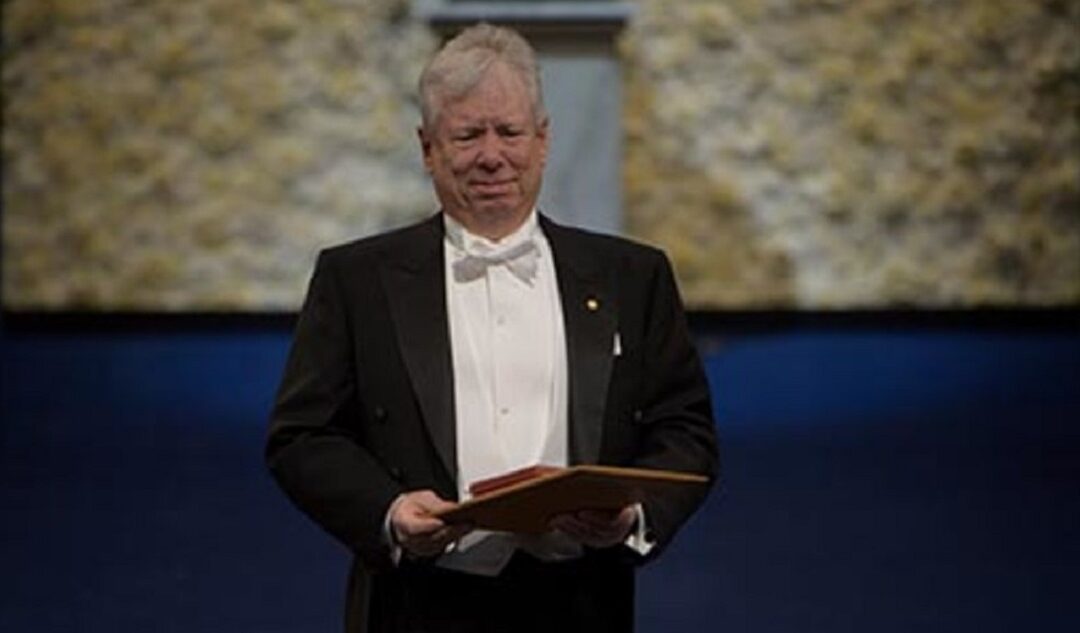

In October 2017, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Professor Richard Thaler, from the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago.

Richard Thaler’s main hobby over the past 30 years has been to poke holes in traditional economic theory. And he’s good at it. Below are some examples of how he did just that.

Economists say humans should think of all their money as one big pile – a dollar in one pile is just as good as a dollar in another pile.

Thaler argued that’s not at all how we think. For example, the money in your cheque account and the money saved for your children’s education are not just perfect replacements for each other. As another example of this, some people keep a big pile of cash in their bank account, earning 1% interest, instead of paying off a mortgage which is costing them 6% in interest. Why? Classical economics has no answer.

Economists say we value goods the same, whether we own them or not.

To challenge this, Thaler randomly gave half his class coffee mugs from the student store. Those who were given a mug valued them at $6; those who weren’t, valued them at $3. Why would owning a mug make it more valuable? It seems irrational to value something more, simply because you own it. Thaler called this the ‘endowment effect’. Thaler also showed that selling something you own feels like a loss, while buying something feels like a gain. We hate losses more than we love gains, which, explains why you’d never call your adviser if your portfolio went up 15%, but you may be inclined to panic if it went down 15%. Classical economics says they are equivalent, but the endowment effect says, emotionally, they aren’t.

Dr Thaler showed, through tests, that the more often you look at your portfolio, the more sensitive you are to loses, the less you want to own shares.

Why does looking at your portfolio influence your preference for shares? Because looking often increases the chances of seeing temporary dips, and dips feel painful. Thaler concluded that the best investor would hardly ever look at their portfolio. Classical economics has no explanation for this.

He noted wryly that, when you go to a dinner party and there is a bowl of cashews on the table, more often than than not you spoil your appetite before the main meal arrives.

In fact, you are probably relieved when the host puts the nuts away. In essence, you are better off not having the choice to eat cashews. Classical economics always assumes more choice makes you happier, but does it?

Thaler pointed out that humans have a penchant for being lazy, so, if you want good behaviour, then make the easy choice the optimal one.

For example, perhaps you should have to opt out of being an organ donor. You still give people choice, but you make the better social outcome the default.

Increasingly, Thaler has shown that humans aren’t rational. We make mistakes. Just knowing that wouldn’t win anyone a Nobel Prize, however, Thaler showed that the mistakes themselves are predictable, and therefore, something could be done about them. This is what the Nobel Prize is for.

By knowing losses hurt more than gains, one could counter that by not looking at their portfolio, and ignoring the news.

Regarding investing, Thaler has said, “Whenever anyone asks me for investment advice, I tell them to buy a diversified portfolio heavily tilted towards stocks, especially if they are young, and then scrupulously avoid reading anything in the newspaper aside from the sports section. Crossword puzzles are acceptable…”

Thaler has long disagreed that share market prices are rational. They can go up more than they should, and down more than they should. Why?

The reason is investors forget about risk in good markets and pile in, and in bad markets, they forget about gains and clamber to get out. In doing so, they make the biggest mistake of all – they tend to buy high and sell low. According to Thaler, we are, by nature, bad investors. Our instincts work against us.

In summary it’s not that we shouldn’t behave rationally and purchase well diversified portfolios, buy more in down markets, resist the urge to pile into good markets, and only ever sell when we need to spend the money…it’s just that doing that, is really hard.

Our head says, I should buy what I know. I should Invest in a few local companies I recognise. Our head says, markets are falling, I should stop my KiwiSaver contributions. Our head says, I should sell my portfolio, after markets have already gone down.

That’s why, as advisers, we’ve learnt that our job is not so much to select great investments, as it is to create great investors. We must guide investors to sometimes do the opposite to what their instincts are telling them to do.

So, Dr Richard Thaler helped us to connect portfolios to people, and for that, he richly deserves the Nobel Prize that he has been awarded.

And, true to form, when asked how he’d spend the money, Thaler quipped, “As irrationally as possible.”